Artist

Emilia Martin

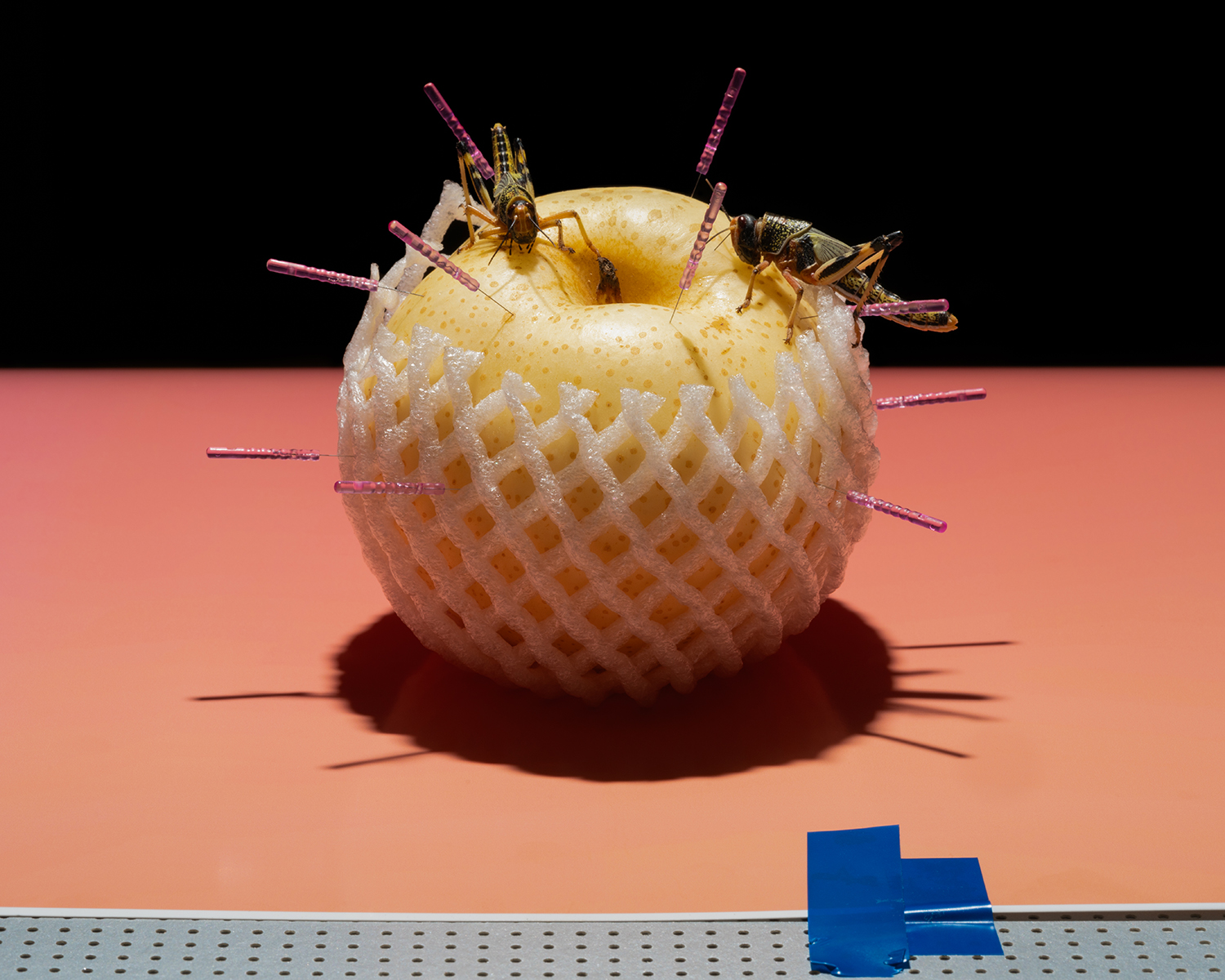

I saw a tree bearing stones in the place of apples and pears

Michał Sita combines elements of photography and anthropology in his work – he looks at people, places and architecture in terms of how we collectively imagine and use the past. His latest long-term project is entitled Historia Polski (The History of Poland) and documents historical outdoor performances organised by volunteers and amateurs to commemorate important events in the country's history. Michał not only documented the events, but also took an active part in them. The project is characterised by anthropological attentiveness, inquisitiveness and curiosity. Thanks to them, Sita created a multidimensional project analysing not only the phenomenon of historical reconstructions, but also prompting reflection on contemporary Polish identity.

Paweł Starzec, like Sita, focuses on long-term research projects in which he uses his experience as a sociologist. His latest project, entitled Anew, has been running since 2013 and documents the transformation of Lower Silesia, a region in Poland with an extremely complex and distinctive heritage. In his work, Paweł is consistent, approaching his chosen topics in a comprehensive manner and combining all this with the excellent skills of a documentary photographer.

Karol Szymkowiak is a self-taught photographer fascinated by the surrealism that can be found in the reality he photographs. His work deals with environmental protection, military and civil defence, and physical and mental immobilisation. The artist's interests are evident in her latest project entitled 0169-8629 5223-01750. It is a story about Lake Powidz and the neighbouring largest military airport in Poland, where a substantial expansion of the US military base is underway. It is a multidimensional project in which the author addresses both socio-political and ecological issues.

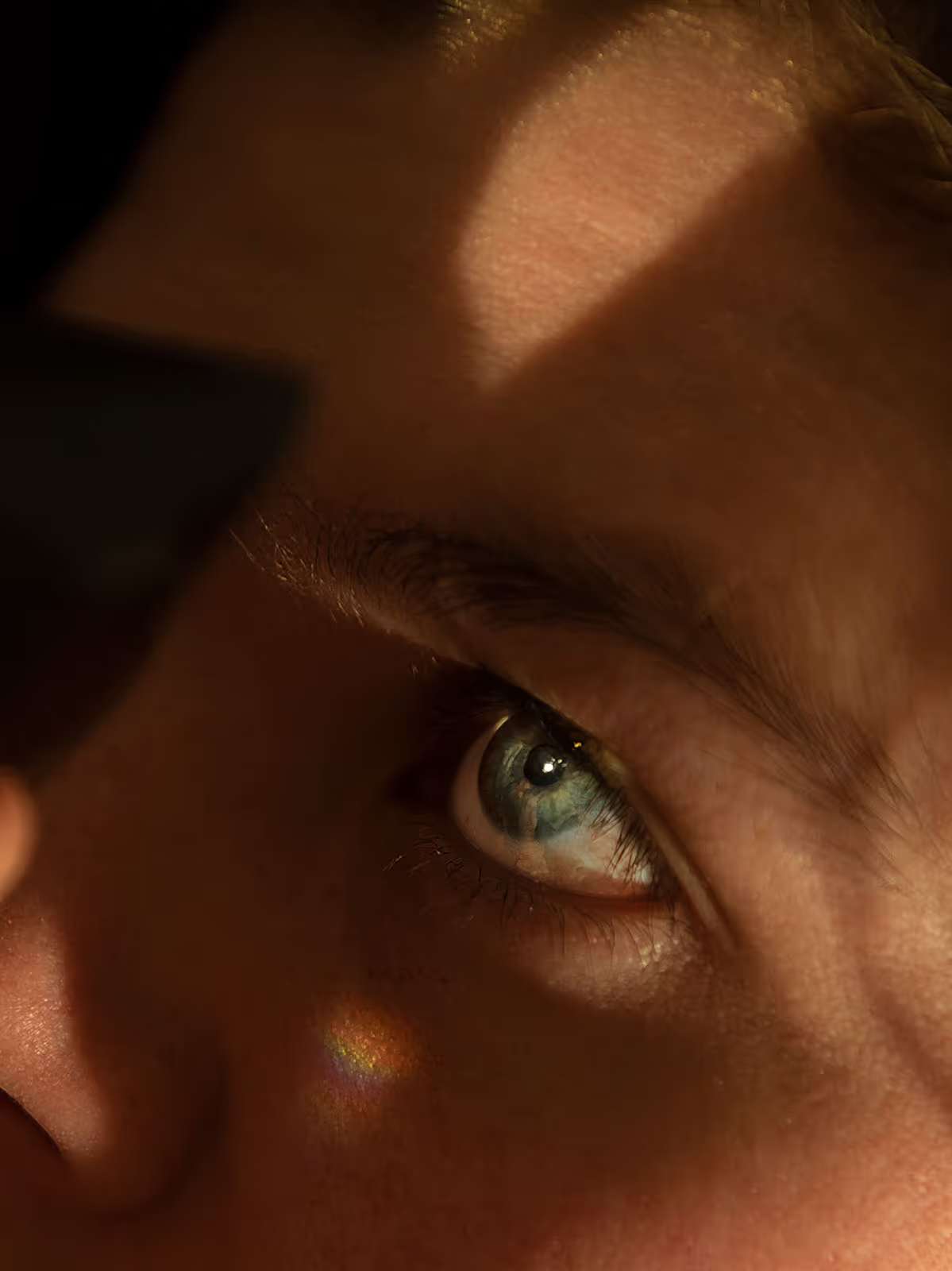

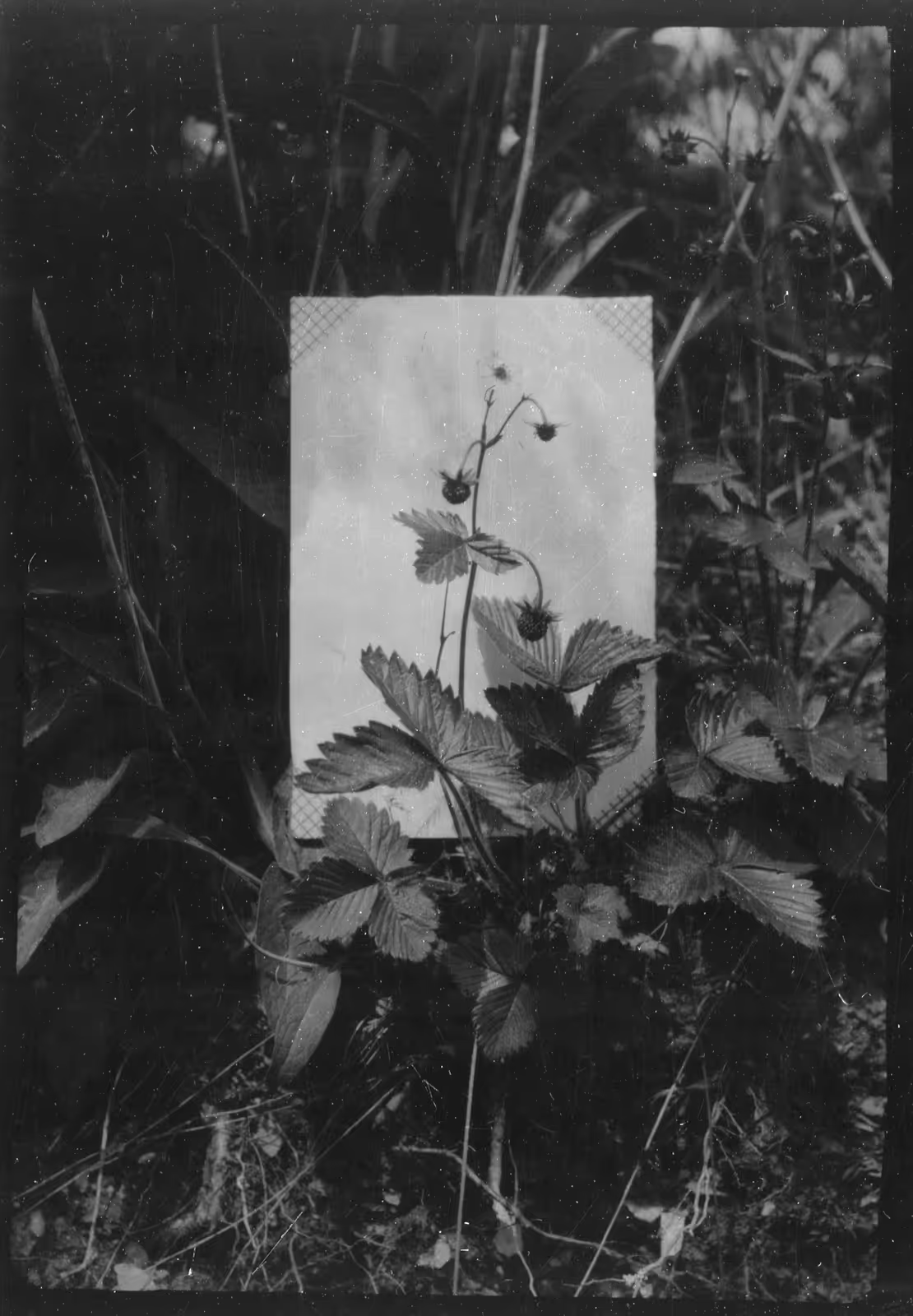

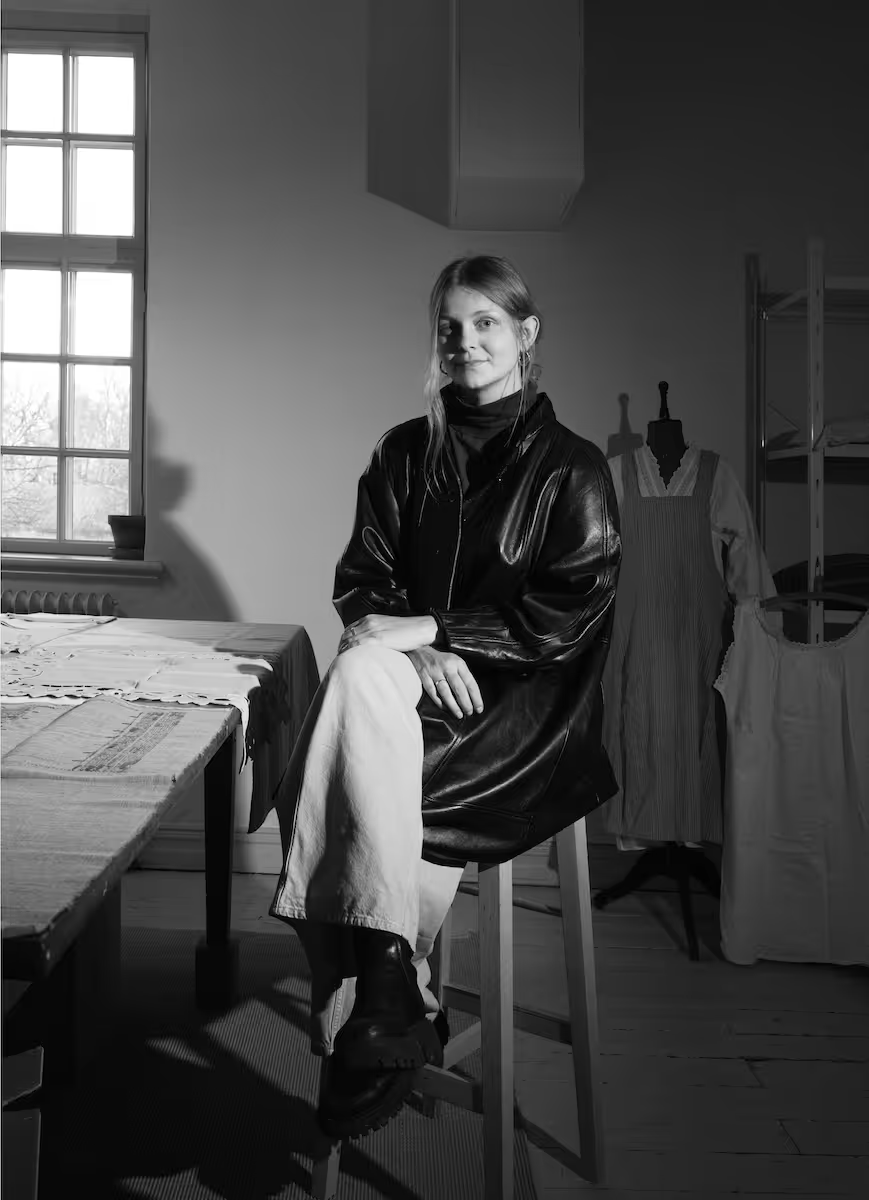

Emilia Martin's work clearly shows the influence of her childhood, which she divided between the natural, rural landscapes of eastern Poland and the heavily industrialised Silesia. In her work, she often draws on the language of myths, fairy tales and stories. It was this fascination that led her to undertake an in-depth analysis of the subject of meteorites in the project, I saw a tree bearing stones in the place of apples and pears. It was this project – based on her own photographs, archival work and sound – that caught our attention. It presents Emilia's unique visual style, exceptional sensitivity and multidisciplinary approach to the subject.

Paulina Mirowska, like Martin, uses photography as one of her media. She works with installations, video, sound and sculpture. She presents herself as a visual artist, burnt-out climate activist and educator – and she uses all these experiences in her artistic work. In her latest project, entitled The Trophy, she tells the story of the beginnings of life on Earth, when photosynthesis appeared in the oceans, enabling the development of living organisms. Mirowska presents this difficult-to-depict process in a way that is extremely evocative and captures the imagination of the audience.

FOTOFESTIWAL :: SELECTING PROCES 2025

STAGE 1

- We created the short list of authors based on:

- selected works submitted to annual Fotofestiwal Open Programme

- nomination of Polish experts; we sent request to 20 experts; 11 answered with the nomination; their names: Łukasz Rusznica, Dorota Łuczak, Adam Mazur, Michał Adamski, Adrian Wykrota, Krzysztof Candrowicz, Małgorzata Słomska, Joanna Kinowska, Nina Giba, Witold Kanicki, Jakub Dziewit

- The shortlist of nominees: 32 people

STAGE 2

- Meeting of jury who selected 5 artists out of the shortlist

- Jury members:

Agnieszka Olszewska [curator; Head of Communications, Exhibitions and Visitor Experience, communication accessibility coordinator in Museum of Photography in Krakow]

Jan Brykczyński [photographer, academic teacher, member of Sputnik Photos]

Marta Szymańska [curator; Fotofestiwal Lodz]