Artist

Milena Soporowska

Trialed by water

Domestic Violence

Handmade Spiritismus

Quarrelsome

Quarrelsome

Yulia Krivich is a visual artist and activist. She comes from Ukraine, but currently lives in Warsaw. In her works, she refers to her own experiences and touches upon the issues that are important to the identity of Central and Eastern Europe. Photography is one of her forms of artistic activity. Her performative actions, in which she draws attention to the presence of migrants in Poland as well as the historical dependencies and the resulting attitude of the Poles to migrants from the East are also hot-button issues in the Polish media. Through her artistic work, Yulia makes consistent efforts to bring the migrant community into the public debate in Poland and supports their integration.

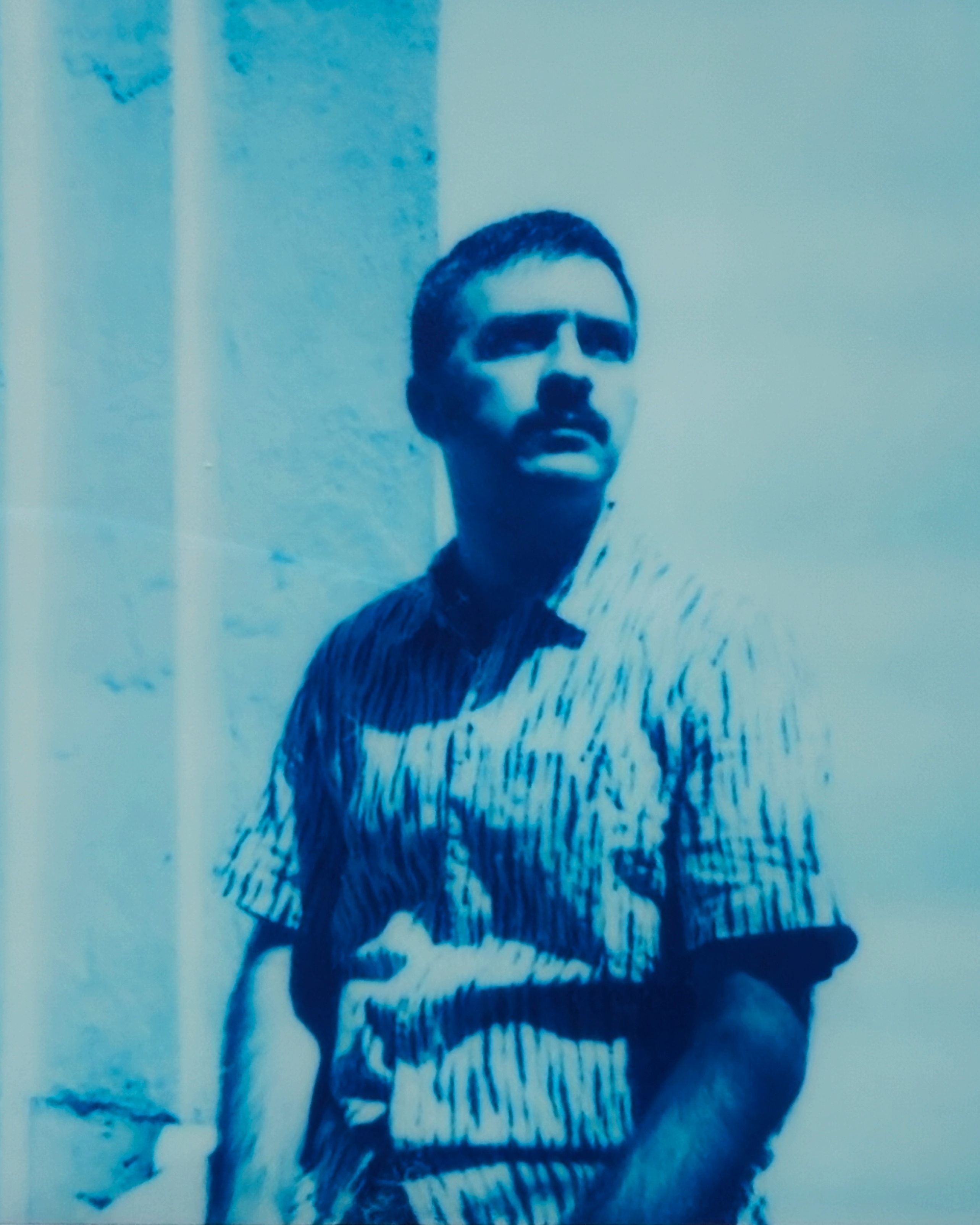

It’s hard to describe the work of Bartłomiej Talaga in just a few words – he is a multimedia artist, musician, photography book designer and a Film School teacher. He is also an exploratory artist. His projects are interdisciplinary – they combine photography, music, multimedia, site-specific actions. Some of his works are also purely visual adventures based on intuition, but all of them are characterized by deep thought, mindful focus and exceptional artistic sensitivity.

“I will be mindful of the here and now” – this phrase repeats like a mantra on the pages of Karolina Ćwik’s album, which is a part of the Let’s build the virus series. Being here and now is probably the only way to survive a lockdown with two toddlers at home. Among the hundreds of “pandemic” projects, Karolina’s photos have a unique dose of emotion in them. There is chaos, fatigue, but most of all tenderness bordering on madness, just like in her previous motherhood project.

Maxim Sarychau is a visual artist and photojournalist from Belarus. In his long-term projects and his work as a reporter, he portrays the violence prevailing in authoritarian systems. He returns to hidden stories and gives voice to the victims. He refers to the history of Eastern Europe, but also documents contemporary events in Belarus, including the peaceful protests that took place in the summer and autumn of 2020 in Minsk after the fraudulent presidential election.

Milena Soporowska works in the field of visual arts and art history. In her artistic and research work, she deals with the interpenetration of esotericism with everyday life and the borders between the sacred and the profane. Each of her subsequent projects is a new chapter in this consistently constructed narrative. Based on detailed research, the author refers to the history of spiritualist movements, but at the same time takes up threads of contemporary spirituality.